At the beginning of February 2016, the four of us—Yui Hashimoto (YH), Magie Ramírez (MMR), Yolanda Valencia (YV), and Trevor Wideman (TW)—had the opportunity to travel to Los Angeles to attend the inauguration of the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin, thanks to the support of the Relational Poverty Network. Hosted by Professor Ananya Roy, the inauguration was titled ‘Urban Color-Lines’ after W.E.B. DuBois’ observation that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” The launch sought to highlight the persisting and shifting ‘color-lines’ of the 21st century in cities across the world, while examining local and transnational movements that resist and challenge eviction, foreclosure, dispossession, and banishment. Over the course of two invigorating days, we moved through “Markets, Race, and the Aftermath of Slavery,” “Right to the City: from [the Global] North to South,” to “Black, Brown, and Banished: Ending Urban Displacement in 21st Century Democracies.” Examining complex processes through a variety of disciplinary and activist perspectives, the inauguration and activists charged the attendees with ways to decolonize the university through “its canons of knowledge and engagement with the lives and histories of subordinated peoples.”

After taking part in the launch, we decided to reflect on our experience by way of authoring a collaborative blog post. An experiment in collective writing, we took turns reflecting on the ideas and moments that intrigued us from the two-day inauguration, each responding to the words of one another, while carrying the intellectual threads of the launch and interweaving them with our own lived experiences. The following is what became of this collaborative process.

“Black, Brown and Banished: Ending Urban Displacement in 21st Century Democracies” program during Urban Color-Lines: Inaugurating the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, February 4, 2016.

YH: Recently I’ve been coming back to paradoxes, in particular the paradox between the murder and oppression of Black and Brown bodies simultaneous with the unprecedented foregrounding of the same bodies in popular culture and social movements. At the same time that countless Black and Brown bodies by the names of Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, Tanesha Anderson (because let’s not forget the murder of Black and Brown womyn), Rekia Boyd, Miriam Carey, and Antonio Zambrano are murdered by the police, movements such as #blacklivesmatter, #oscarssowhite, and #Not1more have put race and white supremacy front and center of the collective imagination. I was particularly reminded of this paradox during our time at Urban Color-Lines because as scholars, we are tasked with understanding the mechanics and logics of white supremacy and social movements that dismantle it while also working within a colonial and white supremacist institution and discipline built on the backs of empire, imperialism, and slavery. Patricia Hill from the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign described the paradox as a challenge to know the culprit at the same time to know resistance and resilience. Ananya reminded us at the beginning of day two that there is an inherent tension between the colonial language of the university and daily struggles. It was in these discussions where I finally put my finger on why white supremacy and not racism: I believe Professor Laura Pulido pointed to the fact that racism implies that only whites reproduce systems and acts of racism, whereas white supremacy implies that we are all implicated in reproducing interlocking systems of oppression; that white supremacy is embedded in everyday practices. Moreover, white supremacy is built into the very institutions and practices in which we are embedded, such as the academy and the judicial system. There is also a psychological dimension to white supremacy that racism chalks up to a system outside of ourselves.

The geographer in me couldn’t help but be thinking about paradoxes at the Japanese American National Museum. Laura Pulido recounted the tumultuous history of the site where Indigenous peoples were removed by Spanish settlers to outside of the city limits, where a Chinatown used to be, where Japanese Americans were removed for internment, where Black residents took their place, and where now internment has been memorialized in place. But this history layered with the micro-geography of the immediate space—a space filled with scholars, activists, and everyone in between discussing removal, displacement, and banishment (including surrounding areas of downtown LA) while sitting in a room with names of philanthropists on the wall—epitomized the critical scholar-philanthropy-activist paradox for me.

YV: Yui, I agree, this conference highlighted crucial paradoxes in the attempt to decolonize the university from within. I was also inspired by the concept of white supremacy as a global neocolonial tool fueled by capitalism. According to Laura Pulido, white supremacy is based on ideology of superiority, power and difference. Such ideology creates certain subjectivities that lead to racist behavior not only from whites to non-whites but also among people of color, as Patricia Hill, Laura Pulido and others pointed out. In other words, all of us are active participants of systems of oppression, as you mention Yui. In this regard, I must disclose how close to my heart this concept (and this behavior) actually hits. I am a Mexican immigrant and live among a big immigrant community in Washington state. Something that I did not have words to describe was how within our community—both in Mexico and the US—we sometimes make racist comments or jokes against those who look indigenous: “Oaxaquitas, con el nopal en la frente,” whatever that means. We strive to highlight our Spanish descent, which happens to be in many cases our abuelitos, while silencing our indigenous abuelitas. When a baby is born one of the first questions, following gender, is whether the baby is white and if he/she has blue or green eyes. It is almost as if these phenotypic features are tied to modernity, beauty and class—something we strive to reach. Learning about white supremacy has been enlightening in my understanding of these ongoing behaviors. Given the global reach of capitalism and how intertwined it is with white supremacy, it seems to me that this ideology is global in scope and thus continues to feed Mexico’s de-indianizing project through the discourse of mestizaje.

What is most scary is that white supremacy has become naturalized, normalized, and engrained in our subconscious through institutional processes including mass media representations, capitalism/consumerism, the law, mainstream academic research, institutions, etc. Thus, the challenge is not just to decolonize the university but also many other systems, especially those that feed white supremacy and ongoing oppression in a seemingly normal way. As Ananya Roy indicates, inequality beyond economic logics has become normalized and it must be challenged at multiple levels and scales. This reminded me of the way in which the state is able to dehumanize over 11 million immigrants by declaring them ‘non-citizens,’ ‘illegals,’ such discourses justify negations of social benefits and basic human rights, while at the same time force such people to work for miserable wages, augmenting white supremacy and privilege for some. All undocumented immigrants have been excluded from the Obama Affordable Care Act and Laura Pulido mentioned that under his administration 4,000,000 people have been deported —banished—they have no place to go. Continual denaturalization, critique, and reframing of such behaviors could be one of the first important steps and role the university could play by supporting and bridging the organization of knowledge and coalitions among oppressed racialized groups as the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy aims to do. As Willie (JR) Fleming from the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign mentioned, we must ask and uncover who benefits from deportations and displacements. Pete White, founder of the Los Angeles Community Action Network (LA CAN), stated that histories of oppression and ongoing displacement matter in coalition building among various groups who have been similarly affected; “we are all relatives,” he said. This phrase was especially inspiring. Building solidarity through common struggles could lead to massive transformational change. The university could participate by helping to keep those histories alive. Further, it should be about both, the type of knowledge and its distribution—what is being taught, to whom and by whom—as Camalita Naicker indicated. For instance, is the university (and education system) currently mostly providing knowledge by and for those who have more than their “chains to lose” (Karl Marx)?

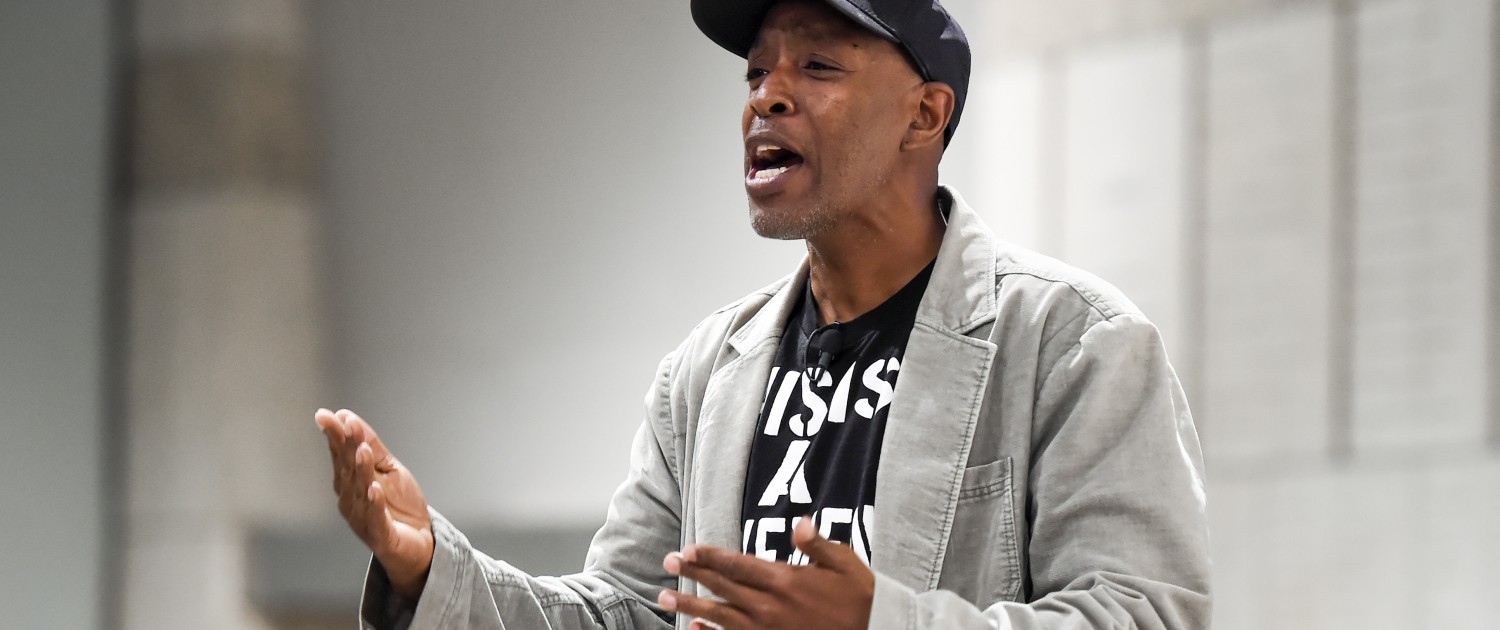

“Black, Brown and Banished: Ending Urban Displacement in 21st Century Democracies” program during Urban Color-Lines: Inaugurating the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, February 4, 2016. (Photo/Gus Ruelas)

TW: Yolanda and Yui, your comments very much hit home for me. In particular, what you said Yui in regards to the amazing “Black, Brown, and Banished” event at the Japanese American National Museum—a place that (as both Pete White and Laura Pulido highlighted) has been, and is very near to, the site of multiple uprootings—including the ongoing displacement of Skid Row residents at the hands of redevelopment. Now, what resonated for me was how the story of Skid Row/Little Tokyo LA bears an uncanny resemblance to that of my current home of Vancouver, where the racialization and uprooting of Indigenous peoples, Chinese Canadians, Japanese Canadians, African Canadians, and low-income residents (among others) from the 1880s into the present narrates a continuous history of colonialism and white supremacy in a province that (as Patricia E. Roy’s work has shown) was explicitly constituted as a “White Man’s Province.” What are the alliances and political movements that can be built by connecting the historical and geographical dots between marginalized communities such as these? Because it’s not just that inequality exists now, or that displacement is happening, it’s that there has been ongoing oppression.

As both of you have touched on, the concept of white supremacy permeated throughout the event. I was absolutely inspired by Professor Cheryl I. Harris and her talk on “Markets, Race, and the Aftermath of Slavery” when she talked about the “market” as part of the constant legacy of slavery and colonialism, framing it a zone where 1) white normativity is constructed, protected, and legitimated as a mode of domination, and 2) liberal regimes of private property are encoded and protected in ways that legitimate dispossession. I also got to thinking about how she spoke about waste, which is a commonplace yet terrible/terrifying word, particularly when applied to a population. She mentioned how “ruin” photos of places like Detroit depict a wasteland, a terra nullius, conveniently devoid of the people of color who majority occupy the crumbling rust-belt cities of the former industrial heartland. We heard stories of waste in relation to the ongoing water crisis in Flint—how one of the poorest cities in the United States is literally being “wasted” as its residents ingest lead-filled tap water. But at the same time as entire populations are being orientalized and depicted as waste, those same populations have enormous utility as a site of capital accumulation—in the form of debt, or within the prison-industrial complex. Yolanda, I agree with what you said about the importance of Laura Pulido’s framing, where she talks about white supremacy as a manifestation of superiority, power, and difference—but it’s the naturalization of that attitude, as you also mentioned, which is perhaps most frustrating, because it makes it so difficult to challenge. In Canada, the conversation around white supremacy feels like it has barely even started, perhaps because the liberal state has done such an amazing job over the past 50 years of convincing us that we are a multicultural and tolerant society, when in fact we are built on overlapping legacies of colonialism, racism, and cultural genocide. And therein lies the question that you both (and in particular Marques Vestal in the “Decolonizing the University” session) touched on: If the university (as a state apparatus) is a site where hegemonic knowledge and power are produced, then how do we decolonize it? How do we decolonize something that it at its core colonial? The speakers in the “Decolonizing the University” session had different answers (and I am super-inspired by what’s going on with the Undercommons at UCLA!), but I kept on coming back to Ananya’s initial query: “If we cannot challenge the university’s role in institutionalizing privilege, then what are we here for?” I would argue that that’s our role as scholar-activists, even though each of us will interpret that role differently.

“Decolonizing the University” during Urban Color-Lines: Inaugurating the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, February 5, 2016.

MMR: Indeed, one of the roles of scholar-activists is to challenge the University’s role of institutionalizing privilege, and to challenge the ways in which we are made complicit to its configurations of power. “No amount of lead water poisoning will douse the fire next time…” spoke Marques Vestal, channeling James Baldwin and his own #gradschoolbrilliance. And the fire next time, the fire that needs to consume and therein decolonize the University, according to Vestal, is made of debtors. To throw a wrench in the entire system of indentured servitude that the University upholds and relies on to function, in which it is almost necessary to indebt oneself in order to access higher education. And what does it mean, asks Vestal, to cultivate social justice agents in the soil of indebtedness? It “atomizes the agitator,” creating a contradictory relationship where the agitator must harbor a relationship to the state to service one’s debt while participating in geographies of rebellion. What, asks Vestal, are the implications for social justice if we are producing a society of indebted people? One major part of decolonizing the University, according to Vestal, is to plan a multidisciplinary boycott and cultural re-articulation of debt. Professor Hannah Appel offered kindling to spark such a fire, recounting the activism of the Debt Collective, which began as a debt strike of fifteen students from for-profit Universities and has now been joined by over 6,000 students leveraging collective power to abolish debt. What sorts of solidarities and collective leverage can be built from such movements? And, how does debt keep us colonized and at the whims of the University’s structure of indentured servitude, and how does this undermine any decolonizing struggles we partake in?

I was intrigued by the words Professor Gaye Theresa Johnson spoke, that as people of color working in the Public University (which is decreasingly ‘public’ if one needs to incur tens of thousands of dollars in debt to participate), “we work in a highly ironic context.” How are the efforts of students and faculty of color seeking to decolonize the University particularly precarious, as we seek to “recreate a space that doesn’t belong to us,” according to Johnson. Are people of color taking a first step in decolonizing the University by simply taking up space in an institution that we were never supposed to inhabit, according to Professor Carlos Vainer?

Representation is a first step, for having faculty and grad student mentors of color opens up a whole other world of possibilities for students of color. It shows that the University can and does belong to students from the margins, that we are not impostors or ‘improper subjects’ (allusions to Cheryl Harris’ discussion of white supremacy and the creation of ‘proper economic subjects’, but I digress). Student protests across the United States in late 2015 reflected this need, not only protesting the racism students of color faced on their respective campuses, but also demanding that the institutions they are paying to attend hire more diverse faculty. These actions are very much about decolonizing the University, demanding that it represent the needs of the student body, and the needs of the United States more broadly as we are set to become a people of color majority nation by 2044. Graduate students and faculty of color do function in the “highly ironic context” of the University, where efforts to decolonize the institution by providing greater access to students from the margins often lead to a ‘diversity fatigue’ that our white colleagues have the option to whether or not to carry. The desire and willingness to increase the diversity of our institutions, to create decolonial spaces on our campuses where marginalized epistemologies are centered and valued, can also work to our disadvantage, as faculty and graduate students of color (particularly women of color) are called upon to do this work time and time again, without sufficient recognition of the literal blood, sweat and tears involved in ‘diversity work.’ Yet we continue to decolonize, we continue to demand that the University make room for the knowledge and needs of those who come after us. We do it for our ancestors and for our children. This struggle comes from a place of decolonial love.

YH: Wow, I wish writing in grad school were more collaborative. It is so inspiring to read and mull over all of your reflections and syntheses and to learn from you all. Thank you for all of your time, energy, and love.

Magie, you’ve ended on a note that I really wanted to explore in this blog post: the affective dimensions of dispossession, banishment, social movements, and scholarship. While my training is very much focused on materiality, the speakers at Urban Color-Lines have really pushed me to consider the affective dimensions of displacement and banishment, as well as the social movements that counter them. Hearing Ashraf Cassiem (Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign), JR Fleming (Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign), Pat Hill (Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign), and Pete White (LA Community Action Network) in particular led me to the understanding that my scholarship is nothing without grasping and documenting affect and non-materiality. Again I come back to tensions and paradoxes, as I felt that they all walked a fine line between energy and hope to resist eviction, displacement, and banishment through various microgeographic tactics like surrounding a house, occupying a house, or putting folks back in their homes, and feeling like gentrification, policing, and the general sanitizing of cities (as in the case of Pete in downtown LA) was in some sense inevitable. I don’t mean to say that they believe sanitization is inevitable, but I more highlight the emotional energy it must take to feel hope in order to resist and mobilize against the relentless and intensifying assaults on poor people of colour in cities across the world. Moreover, I know that universities are implicated in this process of land grabs, dispossession of livelihoods, and despair while also draining the affective energies of people of colour and other marginalized folks within the university (argh, I made the ‘town/gown’ dichotomy…).

I really appreciated Marques Vestal’s reflections on social change “[beginning] at being pissed off and loving,” and that one does not need to know an alternative to fight an injustice. As Magie said, our task as scholars is to decolonize the university “from a place of decolonial love” for both our ancestors and our children. This means that the affective dimensions of social movements and decolonizing the university necessitate knowing and acknowledging the past, but are also wrapped up in futurities and the hope for a more liberatory and just university and city; perhaps one that acknowledges affect. Gaye Theresa Johnson (and Marques) challenged my thinking on this front of hope for the future. Johnson challenges us to “denaturalize the university” by engaging in a “psychic overhaul” of the understanding of the nature of knowledge and knowledge itself. In other words, as other folks, including Carlos Vainer, have mentioned, we must overhaul what we (royal we) count as knowledge, who we count as valid knowledge producers, where those knowledge producers are located, and where and by whom knowledge itself is created. Johnson urges us to let go of distraction if we are to imagine better futures. This requires us to be present and to resist giving in to nostalgia stemming from particular identities and places. When we imagine and hope for better futures, this creates spaces for transnational and/or other forms of alliances that are previously unavailable to the collective imaginary.

“Debtors’ Prisons and Debtors’ Unions: Direct Action in Finance Capitalism” program during Urban Color-Lines: Inaugurating the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, February 5, 2016.

To unite the material and affective, I want to explore more of what Professor Robin D.G. Kelley and Hannah Appel discussed about ‘jubilee.’ In the Bible, Leviticus to be precise (I had to look this up…), approximately every 50 years in Israel, slaves and prisoners would be freed and debts would be forgiven. Appel employs this idea of ‘jubilee’ to discuss various forms of debt and the debt to prison pipeline. However, ‘jubilee’ provides a dual meaning of freeing slaves and prisoners and forgiving debts while also celebrating and feeling a sense of elation after reaching a milestone. I checked out the Debt Collective’s website, and they engage in some of the work that Johnson calls us to do: to get rid of distractions and to imagine, in this case debt, differently by understanding “A jubilee is an event in which all debts are canceled and all those in bondage are set free. It worked in Biblical times and it can still work today.”

So we, whomever and wherever ‘we’ might be, need to give ourselves space and allow ourselves to imagine a different future if we are to decolonize the university, abolish debt, and have a right to the city. As I continue to explore the interplay between the material, affective, and temporal, I want to conclude with some hopeful and inspiring words from Johnson, by way of St. Benedictine, that “always we begin again.” Perhaps this is what inspires activists to continue their tireless work day after day.

YV: Lately I have been thinking: what leads people into activism? I agree that feeling angry and love is empowering as Marques Vestal indicated, and thus affective work is indeed crucial in activism as both of you Magie and Yui mentioned. However, while I hear wonderful things about activism and I have indeed witnessed some powerful marchas, my immigrant community in Washington State does not engage much in them and I wonder why. Some of the reasons might include: unable to afford losing wages, afraid of losing their jobs, risk of deportation and/or incarceration, being already in jail, or not having transportation, or simply not having faith in politicians. Thus perhaps affective work does not only empower activism but it might prevent it, especially if participating puts your own family and community at risk of deportation or unemployment, etc and thus for love, some might not engage…? In other words, I wonder about the power of the oppressive system in making us angry but at the same time creating constraints…

Further, as I was in Los Angeles for the first time, attending the Urban Color-Lines inauguration, I could not stop thinking how could a system be so effective in converting natives to that land into “illegal aliens” who, while exempted from legal benefits, are not exempted from punishment by the law (Cacho 2012)? It was painful to see so many Latinos (mostly women) working in the service and cleaning sector—this was evident in the airport—many of whom are labeled as “illegal aliens” undeserving of social benefits and mobility. Cheryl Harris’ explanation of dispossession and slavery legitimated by capitalist protection of “private property” and that some people enter the market as objects while some enter as subjects was illuminating. It seems that these natives have been converted into objects for the benefit of the market, who not only create savings that are passed on to the consumer and profits for the corporate owners, but also subsidize our shrinking social safety net. As Hannah Appel explained how debt could be re-articulated, from a personal, private and shameful responsibility into a public matter that empowers the debtor and disempowers the lender, I thought about those workers and my immigrant community in Washington and the power they could have if their status was rearticulated from outsiders to natives; and their labor from “unskilled” to essential for the thriving of this country and in creating privileges for its “citizens.” Further, Hannah Appel’s provocations—that if all debtors default in their loan, the lender will not die. But paying off the loan can cost the debtor’s’ life—sparked a few questions: What would happen if all racialized immigrant workers default from their employment? Would anyone die? Who? What would it take for more to get angry enough to mobilize and confront a society that normalizes inequality and protects citizenship—and thus whiteness—as a private property (Cheryl Harris)?

Student and Activists Seminar with David Simon during Urban Color-Lines: Inaugurating the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, February 5, 2016. (Photo/Roberto Gudino)

And it is not that inequality has been simply normalized, the poor have been criminalized. According to David Simon, the racialized poor are being managed with force via the so-called War on Drugs. The poor are both over- and under-policed: Over-policed due to massive surveillance and arrests. This is a win-win for the police because the higher the number of arrests, the more opportunities for job promotions. They also receive larger paychecks as they also get paid for the number of hearings they have to attend. The poor are under-policed because most cases of crime against the poor racialized go unresolved. He encouraged those in power to make decisions in drug cases to think again on whether non-violent charges deserve prison time. I could see the parallels with the War on Drugs in Mexico and agree that it is a way to manage the poor with force, not only within the US but also transnationally. In Mexico, this war has sparked a tremendous wave of violence but also massive resistance and movements across the nation including the Autodefensas which started in agrarian communities in Michoacán, and Los 43 de Ayotzinapa in the state of Guerrero which has leaded to transnational coalitions.

What this inauguration made me realize is that having a space and time for collective reflection, analysis and discussion regarding these issues is an important step towards broader solidarities. However, being in this space is also a privilege that many, especially those being criminalized and forced to work extra hours for miserable wages, do not have. And thus, I agree with you Magie, augmenting recruitment, support and retention of both students and faculty of color is critical not only in decolonizing the university but also in organizing knowledge to challenge inequality more broadly at various levels and scales as per Ananya Roy. While events like this, and several programs—including CAMP, GoMap, MEChA and McNair—provide essential support and community for minority students in the university. The question is, should support from the university begin before college given that students of color face barriers in the education system at earlier stages as well? This question came to me as I hear one of the attendants asking whether decolonizing should include other levels of education…

Cacho, Lisa Marie. 2012. Social Death Racialized Rightlessness and the Criminalization of the Unprotected. New York: New York University Press.

Pulido, Laura. 2007. “A Day Without Immigrants: The Racial and Class Politics of Immigrant Exclusion.” Antipode 39 (1): 1–7.

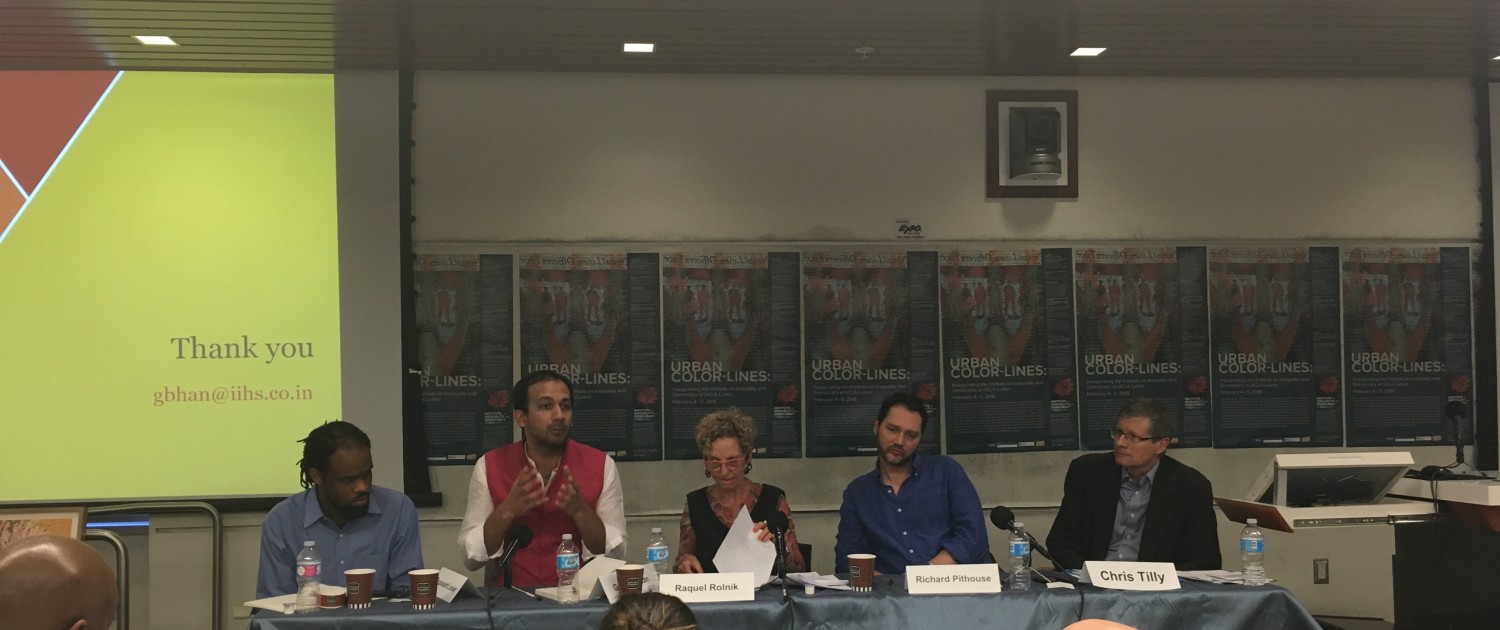

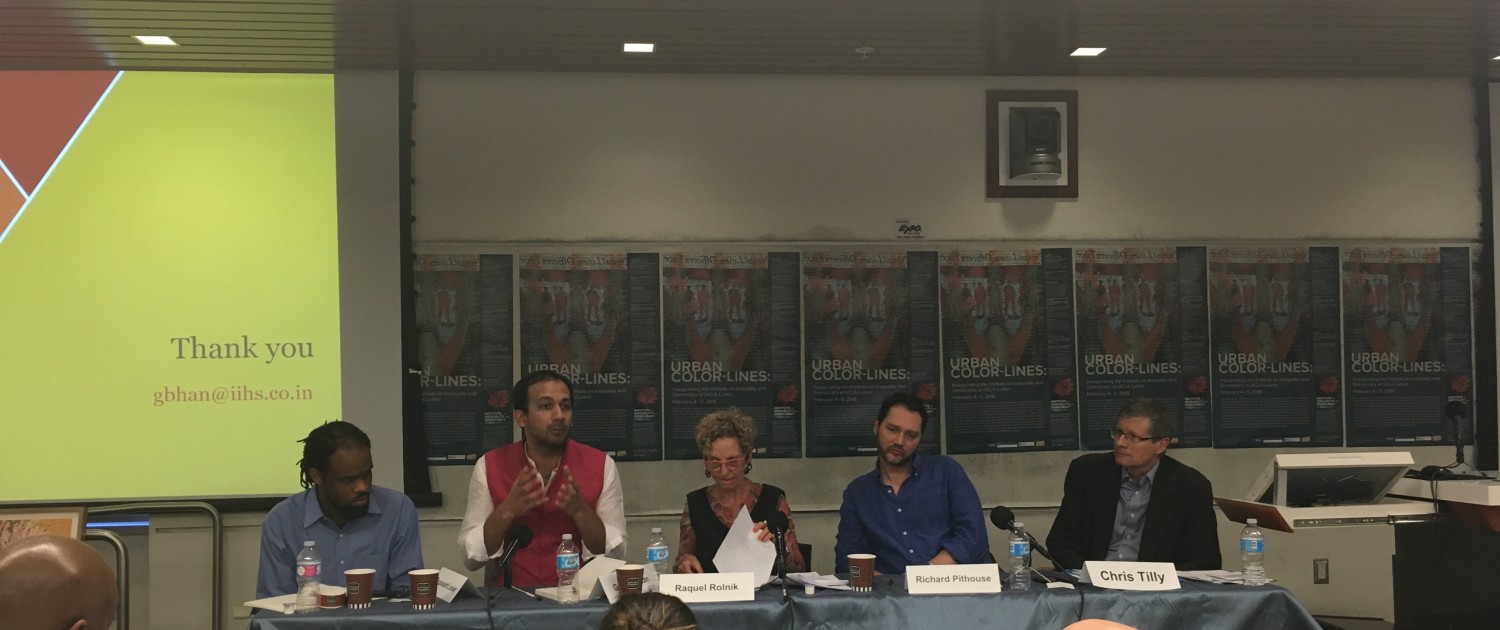

“The Right to the City: From South to North” program during Urban Color-Lines: Inaugurating the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, February 4, 2016.

TW: Yolanda, your question about whether decolonization should include other levels of education reminded me that there are many other sites that need to be decolonized—so many that I began to have a difficult time identifying where to start. Subsequently, I got to thinking about dwelling-places as political sites. All the way through Urban Color-Lines we heard stories of how these amazing anti-displacement movements started, or were nourished, when people’s homes were under threat, and I think that theme ties nicely into some of the points you have all raised. Yui, you talked about the affective experience of those experiencing displacement and banishment—I thought of this as the moment when people’s feelings of safety and belonging “in place” turn to alienation “from place.” Magie and Yolanda, you’ve both suggested the importance of the home and family in relation to ongoing decolonization. When I was struggling with “where to start,” I thought of the ongoing importance of such places of belonging.

Reflecting on “The Right to the City” panel on day one, I thought about the idea of home, or dwelling, as a place from which resistance emerges. Professor Raquel Rolnik stated, channeling Marx, that the so-called “slums” have an important new role for capital as a reserve of land. Urban land is now seen as an abundant source of exchange value, not as a home with use value, and it is always in a state of flux, a process driven by forces of destruction underpinned by a new colonizer, global finance. While this sounded like an impossible juggernaut to stop, I found this panel to be at its core hopeful, because “The Right to the City” (though abstract) holds immense promise for revolutionary action, alliance building, and occupation within the dwelling-places (writ large) where people make and feel home. This seems to me to be a project that is fluid, relational, and concurrent with the project we’ve all been talking about, that is, decolonizing the university, and all these speakers talked about the power of place in mobilizing resistance.

I thought of how Professor Gautam Bhan stated that “a politics of the right to the city must first reframe the presence of the poor in our cities,” and I immediately felt hesitant because of the ways that such politics have in the past been co-opted in ways take representational power away from those activating and mobilizing radical action in place. That said, I think that “reframing” is an important step and Bhan’s point dovetails nicely with what you just said, Yolanda: there really is a deep need for such work because it has the potential to hand significant power back to the disempowered—those who are activating, resisting, working, and living “on the ground” to challenge displacements and inequality. The other speakers also highlighted the importance of work being done on the ground. Even though Racquel Rolnik’s talk focused primarily on the ways that global financial processes colonize the local through land by turning homes into dollars, she also showed how such processes activate resistance movements that can create opportunities for place-based alliances and radical action. Professor Richard Pithouse framed “home” as a fluid, grassroots political site that can create subjects and challenge objectification, as well as the present status quo. Yet perhaps I felt most inspired when Professor Toussaint Losier talked about how meeting with Ashraf Cassiem in Cape Town fueled the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign and their fight against the all-out (and ongoing) attack on public housing in that city. The Cape Town movements highlighted the importance of home and the urgency of grassroots struggle in place and transnationally, and Chicago activists took that inspiration to advance their struggle outwards from the “place” (also home to so many) of Cabrini Green and began building alliances between people being displaced city-wide, despite the limitations of the grassroots in the face of white supremacist legal structures and property regimes. Toussaint’s story made me think further on what you said Yui and Magie regarding the tremendous amount of emotional work involved in decolonization and resistance, and it made me thankful for the powerful affective experiences that come with activist victories (however small or large) against displacement, or against the colonial worlds that we all dwell in. Those moments of hope are surely why many of us continue to spend emotional energy on such projects. All this is not to say that I think that home is the most important site of resistance, but that there are many simultaneous projects of decolonization happening, and that connections and threads need to be woven across worlds. For me, this institute was incredibly inspiring, and it made me think a lot about the possibilities for radical transformation that are available when such alliances are made.

MMR: Your questions and provocations are so necessary, Yolanda. Absolutely, energies to decolonize the university and therein public education more broadly need to address access way before the university level. And there are educators, students and activists that are committed to this work at all levels of the education system, each doing our part to chip away at the educational structures that be. Last year Oakland hosted the Free Minds, Free People conference, a movement that brings folks together to “develop and promote education as a tool for liberation.” I found some of the conversations had in this space to be more boldly decolonial than many I have encountered in university spaces, and the only thing that was lacking was the presence of more university-level scholars and educators. There is a definite need for a conversation on how to connect decolonial struggles from public schools on up to public research institutions. As always the confines of the neoliberal university keep us hanging by a thread and thus we tend to insulate our work, but the decolonial struggle reaches far beyond the walls of the North American university, as Urban Color-Lines showed us, by bringing transnational scholar-activists in conversation. As Trevor mentioned, decolonial struggles emerge from an array of places, and while I summoned intentions from and for our ancestors and children, I wasn’t intending to spin the prototypic wheel of geography where we differentiate between home, university, public space. To be honest, I see decolonial struggles and more profoundly decolonial love to be forces that traverse space, not ones that can be ordered and encapsulated in musty categories. Decolonial love is a force we carry in our bodies, that we channel from our ancestors, that we live, breathe and dance to, a rhythm that we teach to our children. As such, decolonial work is something we must do, or at least strive to do, in all the spaces we engage in—to me it is work that we do constantly, it has no limits or borders, does not obey binaries of ‘public’ or ‘private’.

As Ananya asked us in her opening comments of Urban Color-Lines, ‘What is the politics of hope that is possible and necessary?’ Liberatory and decolonial struggles are grounded in a politics of hope, and require a thick resilience. As you said Yui, it takes tremendous emotional energy to “feel hope in order to resist and mobilize against intensifying assaults on poor people of color across the world”. Where do we find the emotional and bodily fuel to keep fighting? I believe it stems from hope, love, and the same resilience that Patricia Hill summoned. Resilience as the land is being grabbed from under our feet, poor people worldwide being displaced, dispossessed, and banished. As JR so brilliantly stated, “This is not gentrification. Why do you get such a nice word? This is urban economic and ethnic cleansing.” And yet these land grabs are deemed perfectly ‘legal’ by the collusions of those in power. Which raises another thread of provocation that emerged throughout the two days of Urban Color-Lines around the meaning of or boundaries between (il)legality. For if foreclosure, eviction, and redevelopment are upheld as fair and legal, we must acknowledge the different forms of (il)legality that Gautam Bhan raised. Discussing different forms of settlements in Delhi, Bhan articulated that the politics of the right to the city are wrapped up in discourses of (il)legality and (in)formality, for when one speaks of “informality and immediately references the slum, it is a misrecognition for they are both illegal but only one is villainized.” Bhan went on to say that in order to shift the politics of the right to the city, we must reframe the imaginary of the poor. This was also raised by Yolanda in her previous post, who questioned how we might rearticulate the illegality of undocumented migrants and their labor, shifting imaginaries to instead deem immigrants and their presence as a valuable and appreciated part of society. To do so is to resist the precarity that pushes so many (racialized) poor people worldwide into what Cheryl Harris called subprime status, where it is not only the houses and the money of the poor (particularly poor black folks) that are deemed subprime, but their very geographies and bodies. How might succeeding at shifting the imaginaries of the (racialized) poor be a radical politics of hope? And how might a reframing of what and whose actions are (il)legal further fuel this radical politics?

“The Right to the City: From South to North” program during Urban Color-Lines: Inaugurating the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, February 4, 2016.

As Richard Pithouse eloquently raised, the language of markets is inadequate for us to understand our world, for its vocabulary is predicated on racial hierarchies. Quoting bell hooks, Pithouse questioned that if one’s homeplace is the site where African Americans can fully be subjects, not objects, and restore “the dignity that was denied outside,” what happens when one’s homeplace is evicted or taken? Throughout black history, said Pithouse (and, I would add, the histories of indigenous and migrant peoples worldwide), we see cycles of ongoing dispossession, and ongoing struggles to create homespace. As the same peoples are dispossessed of their ancestral lands, taken from their lands, have their homes evicted, land grabbed, communities dispersed, forced to migrate elsewhere to survive, you can see why JR insisted “you do not get such a nice word as gentrification.” This is not gentrification; these are ongoing colonial cycles of racialized dispossession. And among the many survival skills that people of color worldwide have learned throughout colonialism, is the ability to create homespaces when we are denied the right to a tangible home for generations. Perhaps home, the space where we can restore our dignity, then becomes a decolonial space, a fluid space that ebbs and flows. Home can be summoned and materialize in brief, powerful spurts of emotion, a space of commonality, a feeling, an energetic embrace. Home exists in spaces of decolonial possibility, and we must work to create it – to build our future by practicing tomorrow.

Final reflections:

TW: I learned so much from the amazing group of people who participated in Urban Color-Lines, and am deeply fortunate to have been able to share the experience with Magie, Yolanda, and Yui and the broader Relational Poverty Network. I feel slightly overwhelmed, because I left with a deeper understanding of the immense amount of (decolonizing) work that still needs to be done, but I am also hopeful and encouraged because I see the alliances and connections between activists working on similar issues across places. Most of all, I’m thankful for the new opportunities and strength that I’ve felt through the relationships that emerged during my time in LA, and it is because of these that I feel able to sustain the momentum that has been generated through this event.

MMR: Overall feeling grateful for the opportunity to travel to UCLA and take part in two vigorous days of thinking, learning and intersecting. It truly was one of the most stimulating and respectful academic gatherings I have been to in quite a while. I appreciate this process of collective writing as well, and having a space to reflect upon all the brilliance we witnessed at the Urban Color-Lines event. To engage casually yet intellectually with fellow scholars is quite dreamy—you’re right, Yui—if only grad school could be more like this!

YV: It was a tremendous honor and inspiration to be part of this event, conversation and collective writing. And while I might have sounded a bit pessimistic in my reflections, I spoke from my heart issues that make me mourn but also energize me to continue fighting with hope for a better world. Nevertheless, I must acknowledge that my immigrant community are indeed people who fight and thrive with love and care. I owe them so much. I am also grateful to such brilliant activists and scholars for sharing so much wisdom, passion and hope. I am also thankful to Yui, Magie and Trevor for their intellectual insight and support. I hope that this is not the end, but the beginning of a longer transformational conversation.

YH: The opportunity and experience of traveling to UCLA and meeting such brilliant folks couldn’t have come at a better time. I am moved by everyone’s generosity. Magie, Yoli, and Trevor, our conversations, reflections (written and verbal), and love is really inspiring me in my fieldwork and writing. And the myriad folks who participated in the two days in LA, you might not know it, but I am deeply indebted to you for pushing me to expand my thinking, reenergizing me, and most of all, inciting hope in the face of our continuous daily struggles for liberation.

Acknowledgements:

We want to give special thanks to Ananya Roy, Vicky Lawson, and Sarah Elwood for giving us the opportunity and space to think, learn, and reflect with some amazing scholars, activists, and everyone in between, to whom we are also profoundly grateful.

Writers:

Yui Hashimoto is a PhD candidate in Geography at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and is currently in the depths of fieldwork for her dissertation. She is examining the work of the Fight for 15 in Milwaukee, which is a part of a national movement of fast food workers campaigning for $15 an hour and a union without reprisal. Her main interests in the Fight for 15 are in understanding racialized and gendered work and centering the socially reproductive work and everyday lives of fast food workers.

Yui Hashimoto is a PhD candidate in Geography at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and is currently in the depths of fieldwork for her dissertation. She is examining the work of the Fight for 15 in Milwaukee, which is a part of a national movement of fast food workers campaigning for $15 an hour and a union without reprisal. Her main interests in the Fight for 15 are in understanding racialized and gendered work and centering the socially reproductive work and everyday lives of fast food workers.

Magie Ramírez is a PhD candidate in Geography at the University of Washington and a Xicana scholar-activist. She is currently writing her dissertation on the decolonial geographies created by art-activists of color in Oakland, California, and the role of art in social organizing against gentrification and intersecting forms of state violence. When not (s)mothering her daughter or writing in circles, M is working alongside the Oakland Creative Neighborhoods Coalition to enact an immediate moratorium on rent increases for home, arts and cultural spaces in Oakland, and to push local government toward cultural and racial equity.

Magie Ramírez is a PhD candidate in Geography at the University of Washington and a Xicana scholar-activist. She is currently writing her dissertation on the decolonial geographies created by art-activists of color in Oakland, California, and the role of art in social organizing against gentrification and intersecting forms of state violence. When not (s)mothering her daughter or writing in circles, M is working alongside the Oakland Creative Neighborhoods Coalition to enact an immediate moratorium on rent increases for home, arts and cultural spaces in Oakland, and to push local government toward cultural and racial equity.

Yolanda Valencia is a PhD scholar at the University of Washington. As a Mexican immigrant, she has deep passion for issues that affect immigrant communities and racialized ‘minorities’ in the US. Her most recent work looks at how women experience vulnerability across the immigration journey and how these experiences can transform their interpretation of risk and safety in the destination country. She deeply enjoys learning and sharing knowledge, not only in the university but also in her community.

Yolanda Valencia is a PhD scholar at the University of Washington. As a Mexican immigrant, she has deep passion for issues that affect immigrant communities and racialized ‘minorities’ in the US. Her most recent work looks at how women experience vulnerability across the immigration journey and how these experiences can transform their interpretation of risk and safety in the destination country. She deeply enjoys learning and sharing knowledge, not only in the university but also in her community.

Trevor Wideman is a PhD scholar at Simon Fraser University, living and working on Unceded Coast Salish Territories (Vancouver, Canada). He is interested in the social justice implications of urban planning processes on racialized and marginalized neighbourhoods. His most recent work was part of a participatory community research partnership that explored the City of Vancouver’s attempts to use Japanese Canadian heritage as a “revitalization” strategy in the impoverished Downtown Learn about the Relational Poverty Network.

Trevor Wideman is a PhD scholar at Simon Fraser University, living and working on Unceded Coast Salish Territories (Vancouver, Canada). He is interested in the social justice implications of urban planning processes on racialized and marginalized neighbourhoods. His most recent work was part of a participatory community research partnership that explored the City of Vancouver’s attempts to use Japanese Canadian heritage as a “revitalization” strategy in the impoverished Downtown Learn about the Relational Poverty Network.